I started this series — introducing American readers to the Second World War as it was fought years before the United States joined the conflict — with Japan’s 1937 offensive against China. Let’s continue with an invasion that’s probably more familiar to most Americans and Europeans:

Having already remilitarized the Rhineland (March 1936), absorbed Austria (March 1938) and the northern and western borderlands of Czechoslovakia (October 1938), and then occupied Bohemia and Moravia (March 1939), Germany continued its territorial aggrandizement in defiance of the Versailles treaty as the summer of 1939 came to a close. (I’m going to resist the instinct to write “Adolf Hitler continued…”, since this was a foreign policy with deep roots in German history and significant support among German elites, however nervous they were of an Allied response.) After fabricating a series of incidents meant to demonstrate Polish aggressiveness (e.g., at the radio station at Gleiwitz), Germany invaded its neighbor on September 1, 1939.

I trust that the one-sided nature of a campaign that took just over one month for the German military to complete is pretty well-known. If not, casualty figures should make things clear: at the cost of 16,000 dead and 30,000 wounded in its own ranks, the German military and its Soviet allies (see below) killed about 70,000 Polish troops, wounded twice as many and took ten times that number prisoner, and took the lives of up to 200,000 Polish civilians.

But reading the chapter on Poland that commences the narrative in Max Hastings’ Inferno, I realized how little I knew about what happened in September 1939. To some extent, the opening salvo in the war was radically different from what followed, but in a couple of crucial ways, the invasion of Poland quickly set the tone for how the war would be fought everywhere else in Europe.

The reactions of two of the countries that would eventually emergent triumphant from the war may surprise casual historians of WWII. First, the British…

While Britain declared war on September 3rd, the German leadership was caught off guard, though Hastings reports that Hitler recovered more quickly than those surrounding him. Expecting another round of appeasement, Hermann Göring screamed obscenities over the telephone at foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. (The two later got to share the defendants’ box at the Nuremberg trials.) And the prospect of a war with Britain produced a very different reaction from the German people than it had in August 1914. From American radio correspondent William Shirer: “There is no excitement here… no hurrahs, no wild cheering, no throwing of flowers… It is a far grimmer German people that we see here tonight than we saw last night or the day before.”

If you were to merely read the transcript of Neville Chamberlain’s radio address announcing war, you might think that, from the beginning, Germany faced a determined enemy convinced of the rightness of its cause:

We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack on her people. We have a clear conscience. We have done all that any country could do to establish peace. The situation in which no word given by Germany’s ruler could be trusted and no people or country could feel themselves safe has become intolerable.

And now that we have resolved to finish it, I know that you will all play your part with calmness and courage….

Now may God bless you all. May He defend the right. It is the evil things that we shall be fighting against – brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression and persecution – and against them I am certain that the right will prevail.

But anyone who’s listened to that address knows that Chamberlain was already defeated, and he prosecuted the war as indifferently as you’d expect. (“Loathing war passionately,” grumbled Conservative MP Leo Amery of Chamberlain, “he was determined to wage as little of it as possible.”) But the prime minister was hardly alone among British political and military leaders, or the British people themselves. Hastings contends that the guarantees of protection given Poland by Britain and France earlier in 1939 “reflected cynicism, for neither had the smallest intention of fulfilling them: the guarantees were designed to deter Hitler, rather than to provide credible military assistance to Poland” (p. 4), and when Hitler would not be deterred, the “cynicism was breathtaking” (p. 19). When the British delegation fled Warsaw and arrived home, the chief of Britain’s Imperial General Staff complained to its head, the remarkable Gen. Adrian Carton de Wiart, “Well, your Poles haven’t done much.” His own expeditionary force, ill-prepared and languishing in France, had done nothing. But Hastings concludes that “the inertia of the French and British governments reflected the will of their peoples” (p. 19). The British would go down in history for enjoying “their finest hour” in World War II, but that hour didn’t come in September 1939, when civilians saw little point in dying for Warsaw — or in continuing the fight once the Poles were defeated.

Then there’s the Soviet Union… Germany invaded Poland only after striking an eleventh-hour bargain with the regime of Josef Stalin — not merely a non-aggression pact, but a divvying up of Poland. Sixteen days after German troops entered Poland from the west, the Red Army did so from the east — quickly but brutally adding 77,000 square miles and nearly 12 million people to the Soviet empire. Not for the first time in its history, Poland was partitioned by Germans and Russians, who even paraded together in some cities.

About ten weeks later the USSR also invaded Finland (and would soon grab the Baltic Republics). Although it ended up taking 10% of Finnish territory in the peace that followed the so-called Winter War, the Red Army suffered at least three times as many combat deaths as its tiny foe.

And while that performance encouraged Hitler and his generals as they planned for their next invasion in eastern Europe, from September 1939 until June 1941, Germans and Russians worked more closely together than either nation would like to remember:

If Stalin was not Hitler’s cobelligerent, Moscow’s deal with Berlin made him the cobeneficiary of Nazi aggression. From 23 August onwards, the world saw Germany and the Soviet Union acting in concert, twin faces of totalitarianism. Because of the manner in which the global struggle ended in 1945, with Russia in the Allied camp, some historians have accepted the postwar Soviet Union’s classification of itself as a neutral power until 1941. This is mistaken. Though Stalin feared Hitler and expected eventually to have to fight him, in 1939 he made a historic decision to acquiesce in German aggression, in return for Nazi support for Moscow’s own programme of territorial aggrandisement. Whatever excuses the Soviet leader later offered, and although his armies never fought in partnership with the Wehrmacht, the Nazi-Soviet Pact established a collaboration which persisted until Hitler revealed his true purposes in Operation Barbarossa. (Hastings, Inferno, pp. 4-5)

But if the Britain and Soviet Union in September 1939 seem worlds apart from the Britain and Soviet Union of later years in the war, in two crucial respects the first month of WWII offered a preview of what was to come.

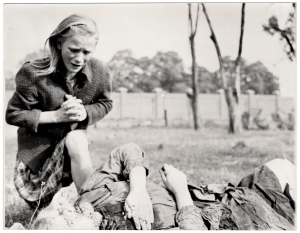

First, Polish civilians were the first to learn that the world of World War II was to be a “pitiless universe,” where the distinction between combatant and non-combatant largely went unrecognized. Hastings tells many such stories, beginning with this account from a Polish cavalry officer who saw a teacher trying to remove her students to the relative safety of the woods:

Suddenly, there was the roar of an aeroplane. The pilot circled, descending to a height of fifty metres. As he dropped his bombs and fired his machine-guns, the children scattered like sparrows. The aeroplane disappeared as quickly as it had come, but on the field some crumpled and lifeless bundles of bright clothing remained. The nature of the new war was already clear. (quoted by Hastings, p. 9)

Carton de Wiart, a veteran of the Boer War and World War I, wrote of September 1939, “I saw the very face of war change—its glory shorn, no longer the soldier setting forth into battle, but the women and children being buried under it.”

None of this was accidental. Just before the invasion, Hitler had told his generals:

Genghis Khan had millions of women and men killed by his own will and with a light heart. History sees him only as a great state-builder… I have sent my Death’s Head units to the east with the order to kill without mercy men, women and children of the Polish race or language. Only in such a way shall we win the Lebensraum we need.

In Inferno Hastings omits the famous next line in this oration: “Who, after all, today speaks of the annihilation of the Armenians?” But he affirms that the most famously genocidal expression of the German quest for “living space” began here, in the fall of 1939, in the country that would host most of the extermination camps: “Within weeks of Poland’s conquest, the first few thousand of its Jewish citizens had been murdered” (p. 24).

Hastings (rightly, I believe) also wastes little time dispensing with the notion that the regular German military fought a decent war for a profoundly indecent government. Appalled that even a general as respected as Erich von Manstein would order his forces besieging Warsaw to fire on refugees trying to escape and write admiringly (even in private) of Hitler, Hastings concludes:

Professional soldiers can seldom afford to indulge emotionalism about the horrors of war, but posterity must recoil from the complacency of Germany’s generals about both the character of their national leader and the murderous adventure in which they had become his accomplices…. In 1939, the officer corps of the Wehrmacht already displayed the moral bankruptcy that would characterise its conduct until 1945. (p. 20)

<<Read the first post in this series Read the next post in this series>>

Where or what is the source for the quote “Genghis Khan had millions of women and men killed by his own will and with a light heart. History sees him only as a great state-builder… I have sent my Death’s Head units to the east with the order to kill without mercy men, women and children of the Polish race or language. Only in such a way shall we win the Lebensraum we need.” – Hitler

It’s been widely used in recent decades, but I think the historian Richard Breitman first discovered it: https://www.deseret.com/1992/4/26/18980798/historian-sheds-light-on-enigmatic-hitler-deputy