Last Friday I decided to put syllabus revision on hold and spend an afternoon continuing my tour of World War I commemoration in the Twin Cities by visiting Fort Snelling, the nearly 200-year old former military installation at the convergence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers that trained officers, processed recruits and draftees, and housed a hospital in 1917-1918. As you’ll see when that WWI commemoration series continues, the visit proved to be a bit of a bust, WWI-wise. But I’m still glad I went that particular day…

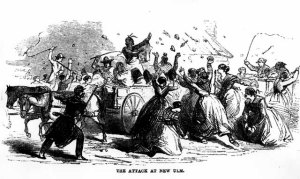

Since last Friday also marked the 150th anniversary of the beginning of a war that few Americans noticed at the time and few remember today, and Fort Snelling played an important role in it. On August 17, 1862, four Wahpeton Dakota warriors killed five white settlers in rural Meeker County, Minnesota, sparking a wave of attacks in succeeding days elsewhere in the Minnesota River Valley. Eventually, the violence spread to northern Minnesota and what was then still the Dakota Territory.

While the Civil War continued with Robert E. Lee’s successful campaign against the Union armies of John Pope in Northern Virginia (Second Bull Run started on the 28th), what’s now generally called the U.S.-Dakota War (or simply the Dakota War) was fought by much smaller forces, but perhaps greater brutality, in the middle of one of the states of the Union. A mark of the relative insignificance (for most Americans) of what was happening in Minnesota is that Pres. Abraham Lincoln chose the disgraced Pope to lead government forces against the Dakota.

In the end, the Dakota were defeated on September 23 in Yellow Medicine County, in a battle that featured no more than 2000 white soldiers and 1200 Dakota warriors. Most of the war party moved to the Great Plains for the winter (and Pope lacked cavalry with which to pursue), but about four hundred were arrested and put on trial for murder, rape, and other charges.

Military courts found over three hundred guilty, often trying the Dakota in groups and taking as few as five minutes to reach a decision. Minnesota’s Episcopal bishop, Henry Whipple, traveled to Washington to meet with Lincoln; he explained to the president that Dakota grievances stemmed in large part from the greed, corruption, and deceit of government agents, traders, and other whites. Lincoln took what he called “the rascality of this Indian business” into consideration and granted clemency to most of those sentenced to die. But thirty-eight Dakota were hanged the day after Christmas, the largest mass execution in American history. (Two more Dakota leaders who had fled to Canada were kidnapped by British agents, turned over to the U.S. government, and hanged at Fort Snelling in 1865.)

(The New York Times‘ Civil War blog, Disunion, has a post today on Lincoln’s role in the Dakota War.)

Meanwhile, about 1600 more Dakota (mostly women, children, and the elderly) who surrendered were held at an internment camp at what’s now Fort Snelling State Park. Perhaps as many as 300 died of malnutrition or measles, and others suffered abuse at the hands of white soldiers and civilians. Amid calls from some white Minnesotans for extermination, 1300 Dakota were expelled from Minnesota; relatively few remain today, the most visible in the Twin Cities being the Mdewakanton (just over 300 people).

It’s a significant moment in Minnesota history, and Fort Snelling (because of its symbolic prominence as the center of white military power in Minnesota in the mid-19th century, the site of the concentration camp, and the scene of the final two executions) seemed like the appropriate place to be for the commemoration of the 150th anniversary. Yet you would barely have known what was happening during my visit: there’s a nice public history display inside the visitor center, but more people were paying attention to the neighboring exhibit about the Fort during World War II; on the grounds themselves, most of the trickle of visitors headed inside to interact with the historical interpreters enacting nineteenth-century life, passing by the information stands outside the fort’s walls that marked the sites of the concentration camp and the 1865 executions.

But for those willing to give it their attention, the anniversary has generated some excellent, nuanced coverage. Last week the state’s largest newspaper, the Star Tribune ran a multi-part profile of the Dakota leader Little Crow, who was famously conflicted about going to war (while he did fight, many other Dakota refused to take up arms and actually protected white friends) and ended being killed in 1863 while picking raspberries. (His corpse was decapitated, his scalp turned in for a bounty.) In association with that series, Twin Cities Public Television aired documentaries on the 1862 war and the scattering of the Dakota that ensued. The Minnesota Historical Society (MHS) has worked closely with historians and activists to commemorate the anniversary, developing everything from an oral history project to an exhibit at the Minnesota History Center to a gallery of paintings by Native American artists inspired by the legacy of the war. And while the anniversary has not been free from controversy (including whether or not to display one of the nooses used to hang the thirty-eight Dakota in December 1863), MHS staff have been forthcoming about the challenge of commemorating this particular event.

Just to write a 500-word summary of the war is difficult: How much background needs to be included to give context for the killings on August 17, 1862 and what followed? Were the 1600 Dakota civilians held at an “internment” or “concentration” camp? (Following the MHS’ lead, I used both terms.) There was ample brutality on both sides, but how much detail belongs in a brief summary?

One of the best pieces that I’ve read on the Dakota War comes from writer and recently retired Dordt College professor James Calvin Schaap, whose essay published at the Books and Culture website (and also at his personal blog) brings those bloody weeks in August-September 1862 to life. (Here’s part one and part two.) In the opening paragraphs, he sketches the events that initiated the war, concluding:

Robinson Jones [the settler at whose homestead the violence began] didn’t ask to be murdered, nor did his adopted daughter. They were victims of what was to them totally unforeseen Dakota lawlessness and brutality.

Or were they? Who of the Dakota had asked white people to take over their land? Who of the Dakota had written up treaties that were sheer lies? Who of the Dakota had asked Europeans to come in and destroy their culture?

The violent opening foray of the Dakota War of 1862 was the vicious, cold-blooded murder of three white men, a white woman, and a white child.

Now, 150 years later, telling the story remains immensely painful, not simply because of hundreds of deaths, but because what happened that August afternoon was the opening round of the Sioux Indian wars across the Upper Midwest, a story of which it can be said that there is no one righteous, no not one. All have sinned.

It’s unlikely to show up in a public history project that caters to a plural society, but I appreciate Schaap’s allusion to Romans 3. There is heroism (Dakota who protected white friends; Bishop Whipple’s desperate attempts to save life) and pathos (the reluctant, honorable Little Crow) here, but we should resist the temptation to shape this history to conform to simplistic narratives of white supremacy (late 19th century memorials erected by white Minnesotans treated the settlers as martyrs and made no reference to whites’ treatment of the indigenous population — for an interesting reflection on what to do with such monuments, see this segment of the oral history interview with Elden Lawrence, a Dakota historian and author of a book on Dakota converts to Christianity and their peacemaking efforts in 1862) or of Dakota victimhood. Truly, “all have sinned.”

At the same time, Schaap warns against the resulting temptation: to treat this history as irreducibly complex and better left unaddressed:

Perhaps the story should simply be forgotten, like some of the old war monuments one can still find throughout the Minnesota River valley. Perhaps some history is better left to crumble into dust, as the bodies of the dead, red and white.

But the 1862 Dakota War is our story—all of ours, and not remembering simply means forgetting.

Oh boo hoo. If I had been an Indian in that time and place, I’d have done what the Indians did. Had I been a white person then and there, I’d have done what the white people did. It was a war. We invaded Dakota land? Cry me a river. Where do you think the Dakota got it? My guess is they drove out some weaker Indian tribe at some point. A handful of Spaniards were able to conquer the Aztec empire, not because they were supermen, but because the Aztec yoke was so oppressive that the Spaniards found allies among subject Indian tribes wherever they went. The Crow fought with Custer because the Sioux had driven them off their land. The Comanche were famous for using fellow Indian tribes as piggy banks for horses, slaves, and prisoners they could torture to death for an evening’s entertainment. We did nothing to the Indians they hadn’t been doing to each other for millenia; we just did it more efficiently and on a larger scale. That’s just the way humanity worked for the first few tens of thousands of years of its history. Anachronistically tsk tsking people who lived in a very different time under circumstances most of us can’t imagine strikes me as a particularly stupid form of political correctness.

Thanks for taking the time to comment, Fred. I’m not going to try to cover all of what you wrote, but I will push back in two related regards… 1. “If I had been an Indian in that time and place, I’d have done what the Indians did. Had I been a white person then…” Please do read Schaap’s article for a more in-depth explanation of what each side actually did. Much of it is horrifying, and disturbing to have someone write off as “It was a war.” At the same time, it was complex, in that people on both sides behaved in a variety of ways. So 2. I’m not certain what “tsk tsking” you think Schaap or I are engaging in, but it’s hardly anachronistic to express concern about the violence in 1862, given that there were whites and Dakota at the time who did far more than “tsk tsk” — they were sickened by what was happening, and expressed it in the moment and in retrospect.

Decrying war and murder is motivated only by political correctness Fred? A “particularly stupid” form of political correctness, nonetheless. This post strikes me only as an evenhanded accounting of an ugly episode of American history.

I don’t think the story should be forgotten at all… that’s why it got FP

http://awesomerockreviews.wordpress.com

Very nice post. It was difficult to read but it is necessary to not overlook the bitter side of history too.

It was good…thanks

Thanks for that post…

Reblogged this on euzicasa and commented:

With God on our side!

Thanks for writing this. I enjoyed it very much and also like and appreciate your perspective. Happy blogging to you and I hope that your article here gets a lot more notice!

A very nice piece. As an expat Minnesotan, it’s been very encouraging for me to read how local organizations are trying to draw attention to the conflict and its history this year; as I wrote in one of my own posts last week, I was fortunate to attend a progressive school district in MN in the early 1990s, where considerable (albeit not quite enough, imo) time was spent discussing Dakota history, including a field trip to the gallows site in Mankato. It certainly influenced my perspective on white-Indian relations, and changed the way I understand the history of western expansion. Glad to see that others are getting an opportunity for even more information on the conflict today. I also want to add another plug for Curt Brown’s series in the Star Tribune, which you highlight here — I found it to be a very well-written and moving series, well worth taking the time to read. Thanks for the additional resources you cite here (Schaap et al), I look forward to reading them!

Thanks for sharing this part of history. I believe that this and other Indian wars are often overshadowed by other history. The Civil War especially overshadows them and many of us only remember the Battle of Big Horn.

I think I m gonna like this blog. Great commentary too. Let’s not forget indeed; for these are the ideologies that holocausts are made of.

Great article, you really did your homework. A few years ago, I recall reading about the Dakota-War of 1862, and even then, I was like,”man, I never heard about this”, but why would I, it’s not like the Western society has promoted the subject of History as an open book. History here, has always been driven towards whatever makes this country look better. Do not get me wrong, I’m recent veteran of the U.S Army, and I’m all for home because this is where I live, but I am not all for the wrongs that have been done. Good work, I’ll follow.

When President Roosevelt’s son asked Winston Churchill – rather rudely – at Yalta “What are you going to do about your Indians?”, Churchill replied “Well not what you did to yours”… I can see what he meant.

Thanks for all the comments, everyone!! I’m really just an amateur on this topic — if you’re looking for real expertise, please check the links I included, or visit the Minnesota Historical Society Press, which has published several books on this war and, more generally, on the experience of the Dakota and other indigenous peoples in Minnesota: http://shop.mnhs.org/mhspress.cfm.

Reblogged this on First American's Society.