It’s probably foolhardy to post on Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway sensation Hamilton. Even if there’s anything new to say at this point, there’s no way to write about something so exhilarating and creative without coming off as dry and trite by comparison. Aaron Burr, the show’s narrator and somewhat sympathetic villain, would no doubt advise me to “Talk less, smile more.” But in the spirit of our voluble protagonist, I’ll throw caution to the wind and toss off a couple thousand words…

I’m not one for delaying gratification. But I somehow summoned the willpower to avoid buying the chart-topping cast recording of the acclaimed musical Hamilton until last month, when I knew that we would need listening material for our cross-country trip to Virginia.

I was not disappointed.

If anything, my kids have become even bigger fans than me. They regularly slip snippets of songs into conversation (the British Invasion sounds of King George’s “You’ll Be Back” make for an especially odd six-year old non-sequitur), and they won’t go to sleep without getting one more play of their favorite high-energy lullabies: the opening number for my son; the Destiny’s Child-like “Schuyler Sisters” for my daughter.

But even if it hadn’t won me Dad of the Year votes, listening so much to Hamilton has been a perfect soundtrack for my sabbatical. It’s the first time in my career that I have no courses in the fall, but Hamilton has got me thinking a lot about history and how it’s taught. Like Hamilton’s sister-in-law Angelica, I realized “Three fundamental truths at the exact same time…”

1. Americanists have it easy

I don’t want to hear any U.S. historian ever again complain about low enrollment in their pre-1865 courses.

As if it weren’t already relatively easier to convince American students to study their nation’s history than that of other parts of the world, now my peers have been gifted with a pop culture phenomenon that has been crafted with history-averse students in mind.

So I’m sorry, but if you can’t use Hamilton to get students excited about the early republic, then you’re not much of a history teacher. (Even if you have qualms with some of Miranda’s historical interpretrations, his work might even make historiography exciting for undergraduates!)

What do we poor Europeanists have? Miranda may have drawn inspiration from Les Misérables for certain parts of Hamilton (fast-forward to the eight-minute mark in James Corden’s Tony-themed installment of “Carpool Karaoke”), but let’s be clear: in terms of lyrical and musical genius, one of these is not like the other.

Maybe I can sneak in the lightning-fast (6 words per second) “Guns and Ships” when I start my week on the French Revolution next fall in HIS354 Modern Europe, rapped as it is by Lafayette (“America’s favorite fightin’ Frenchman!”).

Nevertheless, I’m still entertaining the idea of having some of my students buy the cast album. (Or, Bethel’s largesse permitting, taking everyone on a field trip to Chicago…) Not for any American history course, but as discussion fodder for our department’s Intro to History seminar.

2. Hamilton isn’t a history, but it inspires historical thinking

Over the summer, I wrote a series for The Anxious Bench suggesting some criteria by which we can judge historical movies and TV shows. Hamilton is a particularly good example of the fourth, most important criterion: Does it prompt the audience to engage in historical thinking?

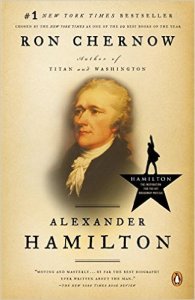

First, I meant that a movie or TV show — or play — should encourage us to learn more from historians. Miranda doesn’t claim that his work is a work of academic history. In an Atlantic interview about the show’s potential to reshape how Americans understand their past, he emphasized that “My only responsibility as a playwright and a storyteller is to give you the time of your life in the theatre.” He clearly tried to be truthful (“I just happen to think that with Hamilton’s story, sticking close to the facts helps me”), but he is not bound by the same rules as historians. So hopefully attending the show, listening to the album, or watching the eventual movie will inspire fans to read the Ron Chernow biography that initially inspired Miranda — or the work of scholars like Joanne Freeman (who apparently features prominently in next month’s PBS documentary on the musical) and Annette Gordon-Reed (who recently reflected on historians’ responses to Hamilton).

But even more importantly, I wrote, “a historical film [or play], made with different rules and goals in mind than an academic history, nonetheless can succeed in prompting us to ‘think historically about the past.'” So I do think it might be a good source to assign in a class like Intro to History, raising as it does important questions about how humans make meaning of the past.

For example: how does the past relate to the present?

I tend to be one of those historians who prefers to emphasize the “pastness of the past,” out of perhaps excessive fear of “presentism.” Hamilton is clearly coming from the other direction. Not only does Miranda utilize late 20th/early 21st century musical forms to tell a late 18th/early 19th century story, but his work is meant to speak into contemporary debates about issues like immigration.

“Our show is not about 1776. Our show is about 2015,” claimed Leslie Odom, Jr. (a Tony-winner as Burr) near the beginning of Hamilton‘s run. “The only reason to keep talking about history is if you are juxtaposing it with the world that we live in today, if you are learning something about our world by looking at the way they shaped their world.” I’d love to hear my Intro to History students respond to that argument…

Then there’s the historical question that runs through the entire play: Who controls history?

3. The people of the past can’t control history — but they’re not entirely passive either

In his rave review for the New York Times, critic Ben Brantley observed: (italics mine)

Mr. Miranda’s Hamilton, a propulsive mix of hubris and insecurity, may be the center of the show. But he is not its star. That would be history itself, that collision of time and character that molds the fates of nations and their inhabitants. You might even call history the evening’s D.J., making sure there’s always something to dance to.

It’s not just that Hamilton is set against a backdrop of enormous political change and intellectual ferment. (“History is happening in Manhattan and we just happen to be / In the greatest city in the world,” sing the Schuyler sisters.) You’ll rarely encounter a play whose characters are so aware, in the words Miranda gives to George Washington, that “History has its eyes on you.”

Of course, one lesson here is that, however skillfully one might participate in Brantley’s “dance,” no one can fully anticipate the future consequences of their actions and ideas. And that includes George Washington. When our first African American president introduced a cast performance of Hamilton at the slave-built White House last year, he pointed to the picture of the slave-owning Washington above him: “I think it’s fair to say our founders couldn’t have dreamt up the future that they set in motion.”

Or as Hamilton muses, as Burr’s fatal bullet hurtles toward him: “What is a legacy? / It’s planting seeds in a garden you never get to see.”

But one’s legacy is more elusive still. Washington also introduces the idea that ends up closing Hamilton: “You have no control: who lives, who dies, who tells your story.”

“[W]hen you’re gone,” asks the cynical, disgraced Burr, “Who remembers your name? / Who keeps your flame?” Or as Brantley put it, “‘Hamilton’ is, among other things, about who owns history, who gets to be in charge of the narrative.”

History, I wrote last year, is an argument:

And, often, an argument about someone — their behavior, their decision making, even their character. In that sense, when historians write history, they are engaging in a potentially aggressive act, struggling with another person for power over the meaning of the past.

Typically, that power struggle seems one-sided. Multiple times (including once last week) I’ve come back to Beth Barton Schweiger’s observation that “I can use the people I encounter in the archives without their consent for my own purposes, for my own pleasures, for my own professional gain. The dead languish without defense in my books; I can even silence them with their own words.”

But Hamilton also suggests that the dead aren’t quite so helpless.

“Don’t be shocked,” Hamilton tells the audience early on, “when your hist’ry book mentions me.” He precedes that boast with a theatrical inside joke: “(Enter me)”, a stage direction that means he is literally adding himself to the plot, telling his own story.

And that befits a character who is obsessed about his legacy, a character who wants to “build / Something that’s gonna / Outlive” him, a character who thinks about the future so often that it already feels like his past. (Hamilton admits as much as he prepares for the battle of Yorktown: “I imagine death so much it feels more like a memory.”)

So this Hamilton makes us wonder how much the actual Hamilton — dead more than two centuries — is still shaping the people who think they get to tell his story, from Ron Chernow and Lin-Manuel Miranda to Joanne Freeman and (now) me. At the very least, isn’t he continuing to advocate for himself through a corpus of pamphlets, articles, letters, memos, speeches, and other writings whose size is matched only by its eloquence?

Or consider Hamilton’s devoted wife Eliza (née Schuyler), who initially seems to care little for legacy — but ends up devoting herself to it.

When Hamilton gushes about “how lucky we are to be alive right now,” it’s because he sees a chance to shape the direction of the future. When Eliza sings the same words, she’s trying to refocus him on the gentler joys of the present. “We don’t need a legacy,” Eliza tells her husband, trying to turn his attention from the problems of the American Revolution to the impending birth of their first child.

Moments later she begs him to “let me be a part of the narrative / In the story they will write someday.” But when Hamilton later lays bare (again, to present and posterity) the sordid details of his extramarital affair in “The Reynolds Pamphlet,” Eliza asserts her power over history by “erasing myself from the narrative”:

Let future historians wonder how Eliza

Reacted when you broke her heart…

I’m burning the memories

Burning the letters that might have redeeemed you

Indeed, she did destroy evidence that would have helped later historians and biographers understand her own thoughts and feelings.

So we’re not sure exactly when, how, or why the Hamiltons reconciled, but reconcile they did. And as the play ends we get a glimpse of how Eliza Schuyler Hamilton planned to control “the narrative” — countering the interpretations proffered by her husband’s political opponents and consciously shaping how later generations made meaning of his life:

I interview every soldier who fought by your side

I try to make sense of your thousands of pages of writing…

“Determined to preserve her husband’s legacy,” writes Chernow, “Eliza enlisted as many as thirty assistants to sift through his tall stacks of papers.” She spent much of her half-century of widowhood advocating for her version of Hamilton’s legacy, and ultimately convinced their son John “to edit Hamilton’s papers and produce a massive history that would duly glorify the patriarch.”

Many thanks to the Genius.com website, whose Hamilton lyrics have been vigorously annotated by a team that includes Miranda himself.

For months I’ve kept something (relatively) secret: I don’t like Hamilton. Too many people around me take it for “real/actual” history and most (but not all) of the music grates on my nerves. Every time Hamilton opens his mouth, I imagine Cell Block Tango playing in the background.

Nonetheless, I appreciate your take on how Hamilton – if used and considered properly – can actually promote history and historical thinking.

I’m also glad you start with something I’ve thought for years: Americanists have it easy.