Before the beginning of the semester last fall, I wrote a post on the challenges (or, as I called them in the post title, “blessings”) of teaching the same course (Modern Europe) year in and year out. Today, the start of our spring semester at Bethel, brings a different kind of problem: teaching a course that I haven’t offered in four years. So please indulge me as I use a blog post to help myself into remembering what I should be doing this afternoon in HIS/POS324G Human Rights in International History.

This was the second new course I developed after coming to Bethel (inspired in part by a Lilly Research Conference on Christianity and human rights), and it alternates with the first, The Cold War. I like the contrast. Both courses are about the history of international relations and the relationship of ideas and ideologies to global politics; both are cross-listed in History and Political Science and fulfill the “Comparative Systems” requirement in Bethel’s general education category. But while The Cold War centers on elites and nation-states that averted war in large part by permitting injustice to prevail (e.g., both sides partnering with dictatorial regimes on the periphery; the West tacitly condoning Soviet coercion in its sphere of influence), Human Rights in International History focuses more on non-state actors like activists and NGOs and how they’ve promoted their visions of peace require justice.

Finally, while the Cold War was one of my primary fields of study in graduate school, human rights is a topic that I teach very much as a non-expert. Which is a useful challenge: it prevents me from falling back into the habit of just talking at students and (especially when it’s been four years since teaching it) instead encourages me to view myself as a facilitator of student discussion and research.

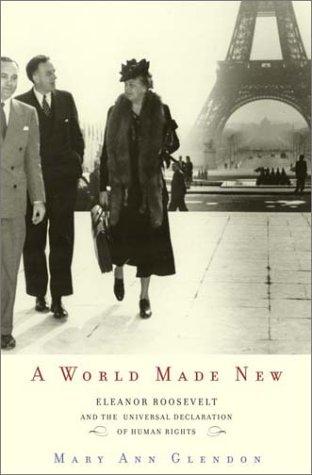

The course is set up in three parts. First, approximately five weeks focused on the theory of human rights — or, more precisely the history of the idea of human rights. While we read from philosophers, political scientists, and religious scholars, one of my prevailing themes here (and throughout the course) is the paradox that rights might be seen as universal or natural and yet still be rooted in the particularity of historical context. Which, my students will soon find, leads many to suggest that “rights-talk” is a cultural construct of Western, Enlightened elites. We’ll explore those questions primarily through reading Lynn Hunt’s Inventing Human Rights, which asks why rights-talk emerged between 1750-1800 in places like France, England, and Virginia, and Mary Ann Glendon’s A World Made New, an account of the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights after World War II. But we’ll also consider more recent expressions (the so-called “third” generation of rights), articulated primarily by Africans and Asians who wanted to restore the balance between individual rights and duties and to protect the rights of entire peoples who had spent decades being exploited first by imperial authorities and then their corrupt postcolonial successors.

The course is set up in three parts. First, approximately five weeks focused on the theory of human rights — or, more precisely the history of the idea of human rights. While we read from philosophers, political scientists, and religious scholars, one of my prevailing themes here (and throughout the course) is the paradox that rights might be seen as universal or natural and yet still be rooted in the particularity of historical context. Which, my students will soon find, leads many to suggest that “rights-talk” is a cultural construct of Western, Enlightened elites. We’ll explore those questions primarily through reading Lynn Hunt’s Inventing Human Rights, which asks why rights-talk emerged between 1750-1800 in places like France, England, and Virginia, and Mary Ann Glendon’s A World Made New, an account of the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights after World War II. But we’ll also consider more recent expressions (the so-called “third” generation of rights), articulated primarily by Africans and Asians who wanted to restore the balance between individual rights and duties and to protect the rights of entire peoples who had spent decades being exploited first by imperial authorities and then their corrupt postcolonial successors.

This year more than others, I think, we’ll also devote several class sessions to the relationship between human rights and the world’s leading religions. If any: we’ll read this essay by philosopher Anat Biletzki concluding that theistic religion and human rights are fundamentally incompatible, multiple pieces on the complicated relationship between Islamic law and human rights — especially those claimed by women and religious minorities, and legal scholar Joel Nichols’ evaluation of what he sees as evangelical ambivalence about human rights — rooted, he concludes, in evangelicals’ relatively weak embrace of the Imago Dei.

After pausing for students to write midterm essays reflecting on such questions, we’ll come back in March-April to take up one of Hunt’s conditions for human rights: that they be politically realized, not merely aspirations or ideals. How have human rights been systematically violated in the age of rights-talk, and how have humans sought to protect against such violations? The abolition of slavery (an international movement — this is very much a study of global and international ideas and movements, not just human rights in one country), the rape of the Belgian Congo (its story told so compellingly by journalist Adam Hochschild in King Leopold’s Ghost), and the genocides of the 20th century will be key stories in this section of the semester.

To get at the question of how best to protect human rights, students will work in groups to study a contemporary issue and propose a response by a U.S. government agency, the UN or another intergovernmental organization, an international court or commission, or a non-governmental organization.

(Students will also have the option to complete their study of contemporary rights protection by conducting a service-learning project with one of the many human rights organizations headquartered in the Twin Cities. In 2008, one student volunteered with the Center for Victims of Torture, while two others used the project to launch a Bethel campus chapter of International Justice Mission.)

(Students will also have the option to complete their study of contemporary rights protection by conducting a service-learning project with one of the many human rights organizations headquartered in the Twin Cities. In 2008, one student volunteered with the Center for Victims of Torture, while two others used the project to launch a Bethel campus chapter of International Justice Mission.)

We’ll conclude in May with presentations by these groups, giving students the chance to learn from and critique each other before their final papers are submitted, then a final essay asking students to reflect on the entire semester. If past history is any guide, a surprisingly large minority will conclude that human rights do not exist (that they are constructed, or impossible to realize), or that rights-talk is not the best expression of justice. Probably more will come away concluding that the challenges of realizing human rights underscore the significance of these words prayed daily by Eleanor Roosevelt (the source of Glendon’s title, and included by her early in the book):

Our Father, who has set a restlessness in our hearts and made us all seekers after that which we can never fully find, forbid us to be satisfied with what we make of life. Draw us from base content and set our eyes on far off goals. Keep us at tasks too hard for us that we may be driven to Thee for strength…. Save us from ourselves and show us a vision of the world made new.