There are lots of factors contributing to the financial crises afflicting higher education in general and my employer in particular. However, since Bethel is a Christian college that has retained more than a nominal relationship with its founding denomination, I’ve sometimes wondered just how changes in Converge Worldwide (Baptist General Conference) have affected our situation. In particular, I’ve wondered how much of our funding comes from the denomination — and how that’s shifted over time.

Fortunately, my colleague Diana Magnuson has been working with our digital librarian, Kent Gerber, and some of our students to digitize records like the Annual Reports of the BGC and make them available through Bethel’s Digital Library. (Special thanks to Fletcher Warren, who worked on the Annual Reports!)

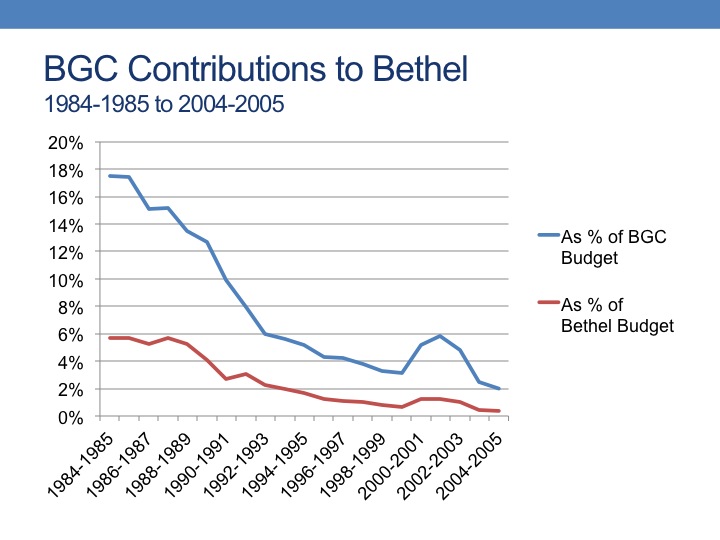

So I started with the most recent such report available online (2004-2005 – Diana informs me that this was the final issue of the Annual) and went back twenty years through the series to chart denominational funding of Bethel. At least, as those contributions were budgeted at the BGC/Bethel annual meetings. (During the 1950s and 1960s — the period I know best — Conference churches rarely met the Bethel giving objective, prompting not infrequent complaints from then-president Carl Lundquist in his annual reports to the BGC.) The graph below shows two percentages: the share of the denomination’s budget allocated to Bethel, the Board of Regents, or “Higher education” (for at least part of this period the BGC was also running Hispanic Bible School — not sure if its budget was lumped with Bethel, or instead under something like “Home Missions” or “Christian Education”) and what that contribution amounted to as a share of Bethel’s budget. On both counts, the change over twenty years was dramatic: (this is a corrected version of an earlier graph whose formatting distorted the figures)

The decline isn’t unexpected (the slight recovery around the end of the 20th century is — I’ll have to investigate further…), but it is bracing to realize just how much has changed in so little time. As recently as a generation ago, nearly 6% my employer’s budget came from its denomination, and that contribution was the third largest line in the entire BGC budget, well behind world missions but nearly identical to home missions. But by the time Bethel College and Seminary became Bethel University in 2004, its denominational support accounted for just over one-third of a one percent of its budget, and that contribution was one of the smallest lines in the BGC — less than a fourth of what was budgeted for ministry service and administrative costs.

Of course, one factor here is that budgets have expanded, far faster than number of church members or college/seminary students even when adjusted for inflation. While the BGC budget increased about 37% from 1984-1985 to 2004-2005, the Bethel budget went up 141% over the same period. Over that time, the BGC’s overall membership grew by 6%, and total enrollment at Bethel increased about 75%, from 2,408 in the lean year of 1983-1984 to 4,210 in 2003-2004.

Meanwhile, the BGC contribution to Bethel, in real terms, dropped by over 85%. (I’m just using a simple CPI calculator to gauge inflation.)

|

Budgeted BGC Contribution to Bethel ($2005) |

Overall BGC Budget ($2005) |

Overall Bethel Budget ($2005) |

|

| 1984-1985 |

$1,937,274 |

$11,072,110 |

$34,132,956 |

| 1989-1990 |

$1,569,015 |

$12,389,433 |

$38,164,422 |

| 1994-1995 |

$743,526 |

$14,393,167 |

$45,105,341 |

| 1999-2000 |

$437,309 |

$13,922,552 |

$63,304,501 |

| 2004-2005 |

$302,400 |

$15,143,600 |

$82,411,431 |

So, how typical is the story of Bethel and the BGC in the world of evangelical colleges and universities and their sponsoring denominations? In tomorrow’s post, I’ll pass along some findings from a recent survey of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU).

At one time, instructors in teaching universities carried heavy course loads and were paid only a little more than a high school teacher. Today, using distance learning technology, the number of students per instructor can be even higher. Universities will continue to offer liberal arts degrees, but the instructors might expect to live in genteel poverty. After all, its a higher calling. Declining hourly rates are affecting many sectors of the economy, so why should higher education be any different?

I’m not sure this post really has much to do with faculty salaries, Jim. (See https://pietistschoolman.com/2013/05/06/how-well-paid-are-christian-college-faculty for an earlier discussion of that issue.) But two responses… First, I didn’t break it down here, but instructional costs have very little to do with the explosion of college/university budgets, certainly not by comparison with debt service and administrative and support costs. Second, there are all sorts of reasons why higher education should be different from other sectors of the economy — see Saturday’s “That Was The Week That Was” for a link to a post on this by Jay Case.

But this raises a broader substantive question beyond what Jim assumes is his narrow concern. What is the promise of Western civilization from pre-Socratic era, through all the different stages of the civilization? Is the point that this is the ultimate trajectory of the civilization “declining hourly rates …. affecting many sectors of the economy?” And yes, Jim has a point although as Chris said, it is not a point that is germane to the main thrust of the article. But I find it still interesting in the sense that I feel people in the Western world have invested so much in history and if the main goal was for humanity to end here as described by Jim, then it is a great disappointment for a civilization that had much to offer humanity at one point. So all this philosophies, revolutions, theologies, histories etc. will just end up at this hopeless juncture? That is the broader issue that is in Jim’s somewhat “take it easy” response, or get used to it attitude towards issues that are of serious concern actually.

In this case, one would have to sympathize with Nietzsche. He in one case asserted that Western civilization is like a ship that has left the harbor going to to the sea (i.e., pursuing modernity). Being confident of the future, the ship owners destroyed the harbor and sailed confidently. But after they have gone too far into the sea, they look ahead and what they saw was infinity and hopelessness i.e., the problem of meaning and direction in life. But the problem is that they are too far from the harbor and even if they wanted to return home, the harbor was destroyed. But to continue the journey in the same path, suggests hopelessness and confusion.

The future that Jim describes is hopeless for not just people in America who have to face this and they are told to face this because the god of the market says so; in this case, the god of the market has more authority than the God of the Bible I will say. Yes, “so why not higher education be any different?” Yet this is part of a broader cultural trajectory and problem. Yes, we cannot go back home, but the future that Jim implicitly endorses is truly unfortunate for not just the present generation but all those who in human history invested their time, resources and sacrificed their lives to create a future that is meaningful and more secure. In effect, this is just saying “get used to it” this is life. Wow. Exactly what is the moral and ethical foundation of such a society, becomes an open question. This is truly a low moment for Judeo-Christian civilization.

If history has anything to teach us, it will be naive to assume that this situation will continue like this indefinitely. The day of reckoning is coming. When and how, I do not know. I do not believe that it will be possible for any society to make everyone equal. Even if that goal was desirable, it is not sociologically feasible. But it will be a terrible mistake for humanity to fold its hands when we have this increasing insecurity on the part of certain segments of the society as Jim admits, while others are living in ivory towers of prosperity. As Charles Murray, the Libertarian warned in his book “Coming Apart,” if this trend persists, the “kinship” we share that is called “American” will be gone one day. We will just be living in the same geographical area but the substance of our lives will be totally different to the point where, the rich in America will have more in common to the rich in other parts of the world, than they do with their compatriots in the U.S. And the church cannot not escape this social reality by simply declaring belief in the Bible and the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Doing so alone will not spare it the social and cultural consequences of such widening inequality. Such inequality will penetrate the church, undermine Christian brotherhood and sisterhood and distort the social imaginary and consciousness of Christians, the exact things that should be shaped by the Gospel. I do not deny the reality of what Jim said. His observation is correct and he is not the first person to say that. My concern however is about whether we should as Americans, human beings and Christians just approach this discussion with an attitude of: this is it, get used to it. So what? We should care, we should act. We may disagree or find it difficult but we cannot afford to fold our hands. What happens in America has consequences in other parts of the world.

I think both you and Jim might find Why Does College Cost So Much? worth reading, Chris. In Bethel’s case, debt service has very little to do with increased costs, for instance. And I think Jay Case, while provocative, doesn’t understand what he’s talking about–but neither do the parents who called his brother. Why Does College Cost So Much suggests, in fact, that instructional costs–in the sense of hiring and paying faculty and providing the equipment they need–have been driving increases for most of the last thirty years. At Bethel, for instance, this may not appear to be very much: the average salary for full professors faculty salary in 1990 was 37,000 for 35 faculty; in 2013, it was 73,300 for 65 faculty. That’s an increase of almost $3.5M, which seems like a small part of a $100M budget. But the faculty jumped in that period from about 110 to double that size.

One thing to consider which is harder to get at than the denominational figure is how much individual churches contribute to the institution. Several churches give astonishingly large gifts on a regular, annual basis.

I’m glad you mentioned individual church gifts, Rich. Given the polity of the BGC, I did wonder if there might not be a fair number of churches that contribute separately. But has that pattern changed much in the past twenty years, such that it would offset the loss of denominational support?

To the question of what causes increased costs in higher education… As I’m sure you know, this is being hotly debated on campus right now, with our finance and accounting professors offering a very different explanation for Bethel’s rising costs, pointing to the growth in “institutional support,” not instructional costs. (I didn’t mean to imply that debt service was Bethel’s particular issue. But elsewhere… http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/14/business/colleges-debt-falls-on-students-after-construction-binges.html.) And as I’m also sure you know, the “Bain Brief” that seemingly everyone mentions in these discussions (http://www.bain.com/publications/articles/financially-sustainable-university.aspx) does not identify rising faculty salaries as a crucial cause of higher ed’s cost problem: “[colleges and universities’] average annual interest expense is growing at almost twice the rate of their instruction-related expense…administrative and student services costs are growing faster than instructional costs” (and see figures 5-6 in that report).

One of the very interesting features of Why Does College Cost So Much is that it looks broadly at higher education and pretty much refutes the “dysfunctional college” argument. Yes, there are particular cases in which institutions are dysfunctional–massive debt, etc. The broad lines of their hypothesis is that higher education costs have risen faster than the CPI primarily because we have been trying to hire and retain people with highly specialized skills at a time when everyone else has been trying to do so, and that increases in the prevalence and use of technology have affected our institutions (and pedagogy) by driving up costs further. The fact that Bethel’s instructional costs recently have been flat might be due to salary freezes, shifts to adjunct faculty, and stability or decline in enrollment. The Bain brief, of course, is one of the “colleges-are-dysfunctional” arguments, but it’s created by people who are offering their services as consultants, not researchers who approach the issue neutrally.

I was curious about inflation after reading Rich’s statement above: “At Bethel, for instance, this may not appear to be very much: the average salary for full professors faculty salary in 1990 was 37,000 for 35 faculty; in 2013, it was 73,300 for 65 faculty.”

According to an inflation calculator, $37,000 in 1989 = $70,418 in 2012.

As compared to what Rich mentions here: $37,000 in 1990 = $73,300 in 2013.

http://www.calculator.net/inflation-calculator.html?cinterestrate=37000&cincompound=1989&cinterestrateout=67173.86852&coutcompound=2012&x=72&y=12

Just adding to the discussion.

I agree with Rich’s suggestion to read the Archibald and Feldman book “Why Does College Cost So Much?” The authors make a very reasoned argument that the issue higher education is facing is primarily a cost disease issue. Our “product” relies very heavily on a highly educated workforce to produce. They compare higher ed to other industries facing similar cost increases, such as dental and legal services. The NYT did a nice interview with the authors: (http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/02/18/why-does-college-cost-so-much/) a few years ago. Other changes I’ve noticed on my campus (St. Scholastica) over the past 25 years is a much larger I.T. department (I.T. folks are typically better educated and paid than the old “secretarial pool” they replaced), the technology infrastructure required to operate a modern college, and a robust office of diversity services (again, highly educated employees) which didn’t exist a decade ago. I’m not suggesting any of these are bad, but they didn’t exist 30 years ago.