How important is St. Augustine, bishop of Hippo? Let’s put it this way… I don’t write and perform parody rap videos for just any theologian-philosopher:

Six years later, that lyric and video don’t seem quite as awesome as they did in the moment. But I stand by this couplet as containing some of my finest writing: “Went back to school in Carthage / (The town the Romans flattened) / And holla! He’s a scholah / in philosophy and Latin.” Anyway, back to the case of Augustine’s importance…

Born November 13, 354 in the Roman Empire’s province of Africa (now Algeria), Augustine became nothing less than the most important Christian theologian this side of the Apostle Paul, and a hinge between the classical age whose decay occasioned his epic City of God and the medieval period during which he was declared a Doctor of the same Church he saw as necessary for salvation. Even secular philosophers admire him, as in the judgment of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “…one of the towering figures of medieval philosophy whose authority and thought came to exert a pervasive and enduring influence well into the modern period… and even up to the present day, especially among those sympathetic to the religious tradition which he helped to shape …. But even for those who do not share this sympathy, there is much in Augustine’s thought that is worthy of serious philosophical attention.”

It’s been said of many other writers (e.g., John Updike, Henri Nouwen, Andrew Greeley), but it seems that Augustine never had an unpublished thought. (I’m not sure how many pages are contained in his corpus, but certainly more than 100 books.) But if his output was voluminous, it was rarely repetitive or dull. The SEP again:

The diversity contained in this body of work defies any easy or succinct synopsis, and anyone who approaches it will find a range of ideas that can alternately intrigue, surprise, and sometimes even disarm and shock. One will also find a range of genres and styles, ranging from texts crafted with great rhetorical subtlety to texts that seem to “jangle” with the “music” [O’Connell 1987, pg. 203] of one who is thinking aloud as he writes. For those who want arguments and evidential support, it is there to be had, sometimes in repetitive abundance; for those sensitive to and appreciative of the power of poetic imagery, that too is abundantly in place. Indeed, as Robert O’Connell says, “Augustine constructed more through a play of his teeming imagination than by the highly abstract processes of strict metaphysical thinking” [O’Connell 1986, pg. 3]. But if that vast, multifaceted corpus is the basis of Augustine’s legacy, it is also the ultimate obstacle to any attempt at neatly packaging or compartmentalizing it within some “ism” that can be neatly taxonomized.

And it’s not all “rhetorical subtlety” and powerfully “poetic imagery.” Here’s a less lofty side of Augustine…

By the same token, it’s likely impossible that anyone could wholly agree with so prolific a writer and rambling a thinker. For example, as I presented an overview of the Holocaust yesterday for my modern European history students, Augustine’s responses to the problem of evil came to mind: e.g., “For the Almighty God, who, as even the heathen acknowledge, has supreme power over all things, being Himself supremely good, would never permit the existence of anything evil among His works, if He were not so omnipotent and good that He can bring good even out of evil. For what is that which we call evil but the absence of good?” (from the Handbook on Faith, Hope, and Love). As always, “the absence of good” seemed too sterile to capture the depravity of the Final Solution. (As Martin Luther said of faith, it seems to me that the evil there was a “living, busy, active, powerful thing.”)

Nevertheless, Augustine is probably the most significant influence on me as a Christian scholar, in ways I can’t begin to perceive and in a few that I can put my finger on. Probably most important is his understanding of how Christians relate to the world, as articulated in City of God. It’s probably familiar to many of you, but I’m still astonished by the subtlety and clarity of Augustine’s mind, and by the enduring relevance of words written almost 1600 years ago…

He starts with the distinction between two “cities” (or, we’d probably say, two populations) that “have been formed by two loves: the earthly by the love of self, even to the contempt of God; the heavenly by the love of God, even to the contempt of self. The former, in a word, glories in itself, the latter in the Lord” (14.28). But while he makes clear that those who love anything other than God cannot build an eternal city, Augustine insists that the City of Man “has its good in this world, and rejoices in it with such joy as such things can afford.” Indeed, “the things which this city desires cannot justly be said to be evil, for it is itself, in its own kind, better than all other human good.” Most importantly, though its inherent, pervasive selfishness makes inevitable that “this city is often divided against itself by litigations, wars, quarrels, and such victories as are either life-destroying or short-lived,” it does seek peace, and that peace — however limited in justice and permanence — is still one of the “gifts of God” (15.4). (Or, as he puts it later, human pride “abhors, that is to say, the just peace of God, and loves its own unjust peace; but it cannot help loving peace of one kind or other. For there is no vice so clean contrary to nature that it obliterates even the faintest traces of nature,” 19.12.)

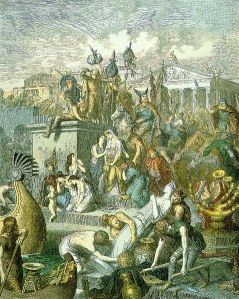

The problem, of course, is that the peace of this world is chiefly attained through violence, or the threat thereof. So Augustine would advise the Roman political and military leader Boniface, in a famous letter written in 418 as the empire continued to crumble under the weight of “barbarian” invasions, that a Christian could (and sometimes should) engage in warfare. The result would be, at best, a temporary peace that paled by comparison with the just, righteous, eternal shalom of God, and yet:

Peace should be the object of your desire; war should be waged only as a necessity, and waged only that God may by it deliver men from the necessity and preserve them in peace. For peace is not sought in order to the kindling of war, but war is waged in order that peace may be obtained. Therefore, even in waging war, cherish the spirit of a peacemaker, that, by conquering those whom you attack, you may lead them back to the advantages of peace; for our Lord says: “Blessed are the peacemakers; for they shall be called the children of God” [Mt 5:9]. If, however, peace among men be so sweet as procuring temporal safety, how much sweeter is that peace with God which procures for men the eternal felicity of the angels! Let necessity, therefore, and not your will, slay the enemy who fights against you. As violence is used towards him who rebels and resists, so mercy is due to the vanquished or the captive, especially in the case in which future troubling of the peace is not to be feared.

The “just war tradition” that Augustine initiated with this letter and excerpts of City of God is currently undergoing revision (as recently described in a two-part post by philosopher Jeff McMahan at The Stone) and others warn that the development of cyberwarfare and drones requires a rethinking of the jus in bello. But I still, regretfully, prefer Augustine’s realism to the idealism of Christian pacifists — particularly of the sort attributed recently to Shane Claiborne, a pacifism that seeks not only for Christians to lay down the sword in all circumstances (which I think is wrongheaded, but understandable), but expects the state to do the same (profoundly mistaken).

Claiborne’s post-Election Day question (“What would America look like if Jesus were in charge?”) should remind us not to put allegiance to Caesar of any variety over allegiance to our Lord (which Augustine also argues, as I’ve written before), but if Keith Pavlischek’s summary of Claiborne’s pacifism is at all accurate, then Claiborne seems to depart not only from Augustine’s position, but from that of the 16th century Anabaptists whose witness he understandably admires: that if disciples of Christ are to turn the other cheek, secular authorities ought not do so. (H/T Joe Carter)

Claiborne, like most modern neo-Anabaptists, on the other hand, insists that the sword is ordained nowhere and never at all. Not only does he insist that Christians repudiate the “violence” of the sword, but that the civil authority do so as well, even in the face of evil, oppression and wickedness. The only moral option for civil authority, according to Claiborne, is some form of “nonviolence.”

Such an option would lead, as Martin Luther — influenced here, as in his soteriology, by Augustine — put it in Secular Authority, to an existence in which “men would devour one another, and no one could preserve wife and child, support himself and serve God; and thus the world would be reduced to chaos.” (All of which makes me wonder if Claiborne’s slogans about “Jesus for president” and the Amish running the Department of Homeland Security are meant as rhetorical provocations, while his actual thought is more nuanced… I’d be happy to have a neo-Anabaptist comment on this!)

And so, Luther writes, “God has ordained the two governments; the spiritual, which by the Holy Spirit under Christ makes Christians and pious people, and the secular, which restrains the unchristian and wicked so that they must needs keep the peace outwardly, even against their will.”

At the same time, Augustine would not have Christians confuse such means or ends for those to which those who glory in the Lord are called. However beneficial the “well-ordered concord of civic obedience and rule” that passes for peace within human history, the City of God “makes use of this peace only because it must, until this mortal condition which necessitates it shall pass away” (19.17).

No matter how Christian their nation might seem in externals such as law and symbols, any member of the City of God lives “like a captive and a stranger in the earthly city.” No matter how stable or long-lasting, no earthly peace should not be confused with the heavenly peace, since no state — no matter how democratic or just — can produce the “perfectly ordered and harmonious enjoyment of God and of one another in God” that is both now and not yet.

Rock on. This made my lunchtime. Thanks.