So I’m sitting at home last Wednesday night. Minding my own business, ignoring the last eight essays that I just didn’t want to grade, eating leftover Halloween candy, watching the CMA Awards because I was too lazy to change the channel after I realized Modern Family wasn’t on… You know, whatever.

Hey wait… Did they just drag Nicole Richie’s dad out for a medley, concluding with Rascal Flatts backing him on “Dancing on the Ceiling”? Did someone named Luke Bryan just do a song called “Country Girl (Shake It for Me)”? And did Taylor Swift just thank TI, Usher, and Ellen Degeneres whilst accepting her Entertainer of the Year award?

What in the name of Ernest Tubb happened to Country & Western music??

I’m not the world’s biggest country music fan, but I do appreciate the genre and hope that my kids are willing to give it a listen. But being a historian, let me suggest that they go all the way back to the twentieth century and check out where country music came from. Here, my highly tendentious picks for the most important country artist and/or album, decade by decade:

1930s: The Carter Family

Amazingly, the first two greatest country acts were both discovered within a couple of days in August 1927 in the same town (Bristol, TN) by the same talent scout (Ralph Peer). First, the yodeling singer Jimmie Rodgers, then the group consisting of Sara Carter, her husband A.P., and his sister-in-law Maybelle. It’s hard now to imagine just how popular the Carter Family were in the 1930s, or how to properly measure their influence on country, bluegrass, folk, and even rock. (The seminal alt-country band Uncle Tupelo, which gave way to Son Volt and Wilco, recorded the Carters’ “No Depression” as the title track for their groundbreaking first album.)

Amazingly, the first two greatest country acts were both discovered within a couple of days in August 1927 in the same town (Bristol, TN) by the same talent scout (Ralph Peer). First, the yodeling singer Jimmie Rodgers, then the group consisting of Sara Carter, her husband A.P., and his sister-in-law Maybelle. It’s hard now to imagine just how popular the Carter Family were in the 1930s, or how to properly measure their influence on country, bluegrass, folk, and even rock. (The seminal alt-country band Uncle Tupelo, which gave way to Son Volt and Wilco, recorded the Carters’ “No Depression” as the title track for their groundbreaking first album.)

I especially love “Can the Circle Be Unbroken,” and the Carters’ recording of it. It showcases Sara’s lead vocals and Maybelle’s tremendously influential style of guitar-playing. And unlike other “escape to heaven” songs in the Christian canon, this one is firmly rooted in the here and now. It might take comfort in the “better home a-waiting / In the sky, Lord, in the sky,” but it’s full of poignant details about the effects that the loss of a loved one (the narrator’s mother, in this case) have for those left behind. See the last verse, for example:

Went back home, Lord

My home was lonesome

Yes, my mother she was gone

All my brothers, sisters crying

What a home so sad and lone

1940s: Hank Williams, Sr.

Unfortunately, Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys have to fall through the cracks here, despite having invented Western Swing, an appealing, unlikely fusion of cowboy tunes and jazz. They peaked in the late 1930s, but not enough to supplant the Carters, and their popularity didn’t really survive the onset of WWII. And this would be a pretty silly excuse for any kind of country music history post if it didn’t pay due respect to the greatest country singer-songwriter of them all.

His career took off in 1947 but only lasted about five years before he died at age 29. But during that time, Williams recorded eleven #1 Country & Western hits, including “Lovesick Blues,” “Cold, Cold Heart,” “Hey Good Lookin’,” and “I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive” (released the year before he died). Another two dozen Williams’ recordings reached the Top 10 on that chart.

His career took off in 1947 but only lasted about five years before he died at age 29. But during that time, Williams recorded eleven #1 Country & Western hits, including “Lovesick Blues,” “Cold, Cold Heart,” “Hey Good Lookin’,” and “I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive” (released the year before he died). Another two dozen Williams’ recordings reached the Top 10 on that chart.

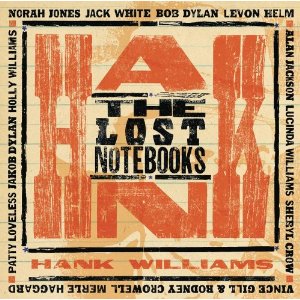

Astonishingly prolific (though also prone to copying existing melodies, his own and others’), Williams left behind unrecorded lyrics that have recently been set to music and recorded by Bob Dylan, Lucinda Williams, Merle Haggard, Norah Jones, Vince Gill, Sheryl Crow, and others.

1950s: Johnny Cash

As it happens, Johnny Cash (who married Maybelle Carter’s daughter, June, and recorded several Carter Family songs) follows immediately after the Carter Family in my copy of the All Music Guide (bought back before it existed as a website). His entry (written by Hank Davis) begins: “It’s almost un-American not to like Johnny Cash. He sings songs about trains and God and farmers and Indians…. The trick is to get past the myth and all the hype and just listen to some of the music.” And the guide suggests starting with The Sun Years, a 1990 retrospective compiling Cash’s best recordings for that famous Memphis label.

Still good advice. The first four tracks are “Folsom Prison Blues,” “Hey Porter,” “I Walk the Line,” and “Get Rhythm.” And if you listen to those four and aren’t exhilarated… Well, just stop reading this post now; you clearly won’t enjoy country music.

1960s: The Byrds, Sweetheart of the Rodeo

Conscious of the fact that I’ve subtitled this post “Country and Western,” let me turn to the West Coast for the 1960s. I’d certainly recommend Merle Haggard and Buck Owens (the latter was both covered by the Beatles — well, Ringo — and name-checked by Creedence Clearwater Revival). But I’ll go with a single album here, out of historic significance even more than artistic merit.

If all you know of The Byrds is the Rickenbackery tones of “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Turn! Turn! Turn!”, dig deeper into their catalog and pick up this album, which effectively marked the birth of country-rock. (And the death of The Byrds as a successful recording group — attempting to bridge the two genres, they found little support from fans of either.) Now, this also means that they paved the way for the Eagles, but Sweetheart more than made up for that sin by introducing the world to Gram Parsons, who introduced the world to Emmylou Harris.

(This album also introduced me to the Louvin Brothers, whose “The Christian Life” is covered on the third track. They’re not significant enough to beat out Johnny Cash for the 1950s slot on this list, but they’re my favorite duo in country music history. And “The Christian Life” comes off my favorite of their albums, Satan Is Real, best known for its cover art, but also home to some excellent country gospel songs like the title track and “Are You Afraid to Die?”)

But I digress… Sweetheart of the Rodeo itself is pretty special — especially if you take advantage of later CD reissues and replace some of the Roger McGuinn lead vocals with the original Parsons takes — romping through everything from honky-tonk to ballads to Woody Guthrie, plus the three tracks that actually blend country and folk-rock (the two Bob Dylan covers, plus the Parsons original “One Hundred Years From Now”).

But I digress… Sweetheart of the Rodeo itself is pretty special — especially if you take advantage of later CD reissues and replace some of the Roger McGuinn lead vocals with the original Parsons takes — romping through everything from honky-tonk to ballads to Woody Guthrie, plus the three tracks that actually blend country and folk-rock (the two Bob Dylan covers, plus the Parsons original “One Hundred Years From Now”).

Just a decade earlier, the biggest rock’n’roll star (Elvis Presley) and the biggest country artist (Johnny Cash) had shared the same label and toured (and, for at least one famous session, recorded) together. So it says something about America in the 1960s that a reintegration of those two genres would have struck anyone as controversial. But the Byrds’ reception by Nashville elites like DJ Ralph Emery was so dismissive that it inspired McGuinn and Parsons to collaborate once more before the latter quit the band and write one of the great disses in American popular music history, “Drug Store Truck Drivin’ Man.”

1970s: Loretta Lynn

Ryan Adams has opened his mouth a lot in his life, so chances were good that he would say at least one insightful thing. Here it is: “Loretta Lynn is punk rock.”

I’m not sure there’s been another #1 American recording artist whose candor has matched their success. But I also don’t know of another such artist from the 1970s so bracingly honest that, decades later, she elicited starstruck admiration from post-grunge types like Adams and Jack White (who produced her scintillating comeback album, Van Lear Rose). She even managed to score a #1 hit in 1971 singing a song by Shel Silverstein (!) that mentioned birth control (“One’s on the Way”), and then four years later to chart with a song entirely about birth control (“The Pill”).

1980s/1990s: Steve Earle and Lucinda Williams

I don’t really want to talk about the 1980s and Nashville, so I’ll cheat a bit and lump together two alt-country legends who debuted in the 1980s but did their best work in the following decade. Steve Earle broke through with 1986’s Guitar Town and continued to explore the boundaries separating country, rock, bluegrass, and other roots musics, but a heroin addiction led to a prison sentence in the early 1990s. Remarkably, he reemerged sounding better than ever, releasing his two greatest albums within eighteen months of leaving jail: Train a Comin’ and I Feel Alright.

(From the decade I should also mention Earle’s 1999 bluegrass collaboration with The Del McCoury Band, The Mountain, if only for its reference to the city where the Carter Family was discovered: “I walked around in Bristol town a bitter broken man / A heart that pined for Carrie Brown and a pistol in my hand.” The verse wraps up with one of my favorite country music lines ever, alluding to the fact that Bristol straddles two states: “We met again on State Street poor Billy Wise and me / I shot him in Virginia and he died in Tennessee.”)

I Feel Alright ended with a duet with Lucinda Williams, who had first released a record in 1979, but didn’t break through until her self-titled 1988 album. Then her two best albums arrived in the 1990s: Sweet Old World in 1992 and six painstaking years later, the landmark Car Wheels on a Gravel Road (parts of which Earle produced). Imagine if Loretta Lynn were from Louisiana and not eastern Kentucky, and had been the daughter of a poetry professor and not a coal miner, and you’ll get Lucinda Williams.

Nothing profound to say, but I went to college and seminary no farther than thirty miles from the sign in the last picture. When it accompanied the blurb on FB, I figured you were headed down to my old stomping grounds. 🙂