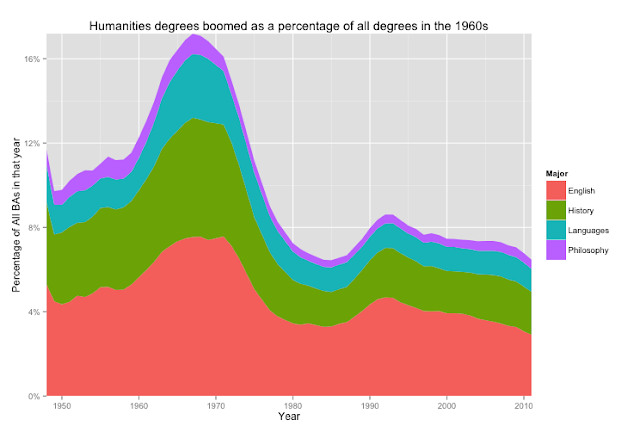

It happened again this summer. I was faced with further evidence of declining enrollment in history, English, philosophy, theology, and other humanities disciplines at our institution. So after making a few other arguments, I arrived at my typical last line of defense: “Anyway, these things are cyclical. The humanities will come back. Just look at this graph.”

The generally downward trajectory of History and other majors is not stellar news for people like me, but you can see that humanities have gone through periods of fall and rise for decades now. If those majors recovered after plummeting in the 1970s, why couldn’t the same thing happen in the 2010s? We might never be back at the peak of the 1960s, but we could certainly get back to where we were just after the Cold War, right?

So it’s troubling to read the most recent analysis from Ben Schmidt, the Northeastern University history professor who produced the graph above:

…something different has been happening with the humanities since the 2008 financial crisis…. Almost every humanities field has seen a rapid drop in majors: History is down about 45 percent from its 2007 peak, while the number of English majors has fallen by nearly half since the late 1990s. Student majors have dropped, rapidly, at a variety of types of institutions. Declines have hit almost every field in the humanities (with one interesting exception [linguistics]) and related social sciences, they have not stabilized with the economic recovery, and they appear to reflect a new set of student priorities, which are being formed even before they see the inside of a college classroom.

Schmidt had more cautious than some of us in describing the situation, but now he concludes that “the drop in majors since 2008 has been so intense that I now think there is, in the only meaningful sense of the word, a crisis. We are in a moment of rapid change. The decisions we make now will be especially important and will have continuing ramifications for what American universities look like for years to come.”

If you teach in the humanities, work anywhere in higher ed, or are a new student trying to choose a new major, you should read the full article. Let me just pick up on Schmidt’s most important point:

There are many possible explanations for why the humanities are failing, but he found it easy to suggest potential defeaters for most of those arguments. Want to blame the failure on the supposed politicization of the humanities by leftists? Schmidt would want you to explain why so many fewer students at conservative religious schools like Bob Jones and Brigham Young are majoring in those fields nowadays. Want to chalk it up to anxiety about debt? Then tell him why history, English, etc. are down at institutions as unlike each other as Princeton and the College of the Ozarks, where (for very different reasons) few students take on significant debt.

Schmidt does allow that students are turning to other fields because of concerns for jobs, but adds “an extremely important caveat: Students aren’t fleeing degrees with poor job prospects. They’re fleeing humanities and related fields specifically because they think they have poor job prospects.”

If, Schmidt points out, students are making the major decision based on what we’d think of as objectively economic factors like employment prospects and likely early-to-mid-career salaries, then why are so many going into fields like psychology and communication studies, whose graduates do worse than most humanities by these counts? Even biology and many business fields are basically on par with fields like history and literature. Where there’s a difference, it’s within the margin of error in most such studies, and shrinks at mid-career (for reasons I’ll come to in a moment).

Now, I assume that few of my readers are actually 17-18 year olds. But some of you are parents of high schoolers, and mothers (especially) and fathers remain the biggest influences on new college students’ decisions. In fact, I think you could almost substitute “parents” for “students” in the “job prospects” quotation above.

So, parents, I get that many of you think majors like history have poor job prospects. But let me tell you why it actually makes good, if counterintuitive, economic sense for you to strongly encourage your student to consider such a field of study.

It’s the least risky way to prepare for employment in the 21st century economy.

I know, I know: it seems risky to pick a major that doesn’t have an obvious pathway to a particular career. But hear me out…

First, you need to recognize that there may be a significant disconnect between your expectations for your kids and their actual working futures. If you’re a 40- or 50-something, you probably retain at least some sense of what it meant to grow up in an economy whose workers stayed in or close to one career, sometimes even at one or two employers, and retired at age 65. None of that is likely to be true for your child as she starts college in 2018.

On the other side of her college graduation is much less stability in employment at virtually every stage of a much longer work life. What else would you expect when life expectancy is increasing, technological and cultural change is accelerating, and both employers and employees seem to be interested in building a “gig economy” that doesn’t assume long-term working arrangements?

So while a college education remains one of the biggest investments of anyone’s life, it’s hard to know how best to use those expensive years to set someone up for future economic success. Do you encourage your child to pick a major because it aligns most closely with a career whose short-term employment prospects look good? You can… but they’ll risk joining a glut of increasingly similar candidates seeking jobs in a market whose bubble may well burst.

Instead, it might make longer-term sense to consider a major in a humanities field, for three reasons:

1. Focusing a significant (though not total) part of her undergraduate studies on something like history, philosophy, literature, or languages is very likely to equip your child with generally applicable skills, mitigating the risk that her college-age career preparation will be rendered obsolete by fluctuations in the job market. If she picks a humanities major and work hard, I can virtually guarantee that she’ll wind up a better reader and researcher, a better analyst and interpreter of data, a better writer, and a more empathetic person who better understands co-workers and clients from multiple backgrounds. While those majors don’t translate as directly into narrow career paths, there are precious few employers who don’t want that set of skills…

2. …and they’re also exactly what your child will need to continue their education later — as she’ll assuredly have to do, one way or another. There’s a reason so many history majors, for example, see a spike in their mid-career earnings: they’re well prepared to do the reading, research, and writing necessary to complete a J.D., M.B.A., or other advanced degree. But even if your kid isn’t going to need formal graduate training, she will need to keep updating their skills and knowledge, and often with less and less external support. She needs to spend her undergraduate years learning how to learn so she can eventually do it on her own.

3. Humanities majors are small, typically taking up only 25-30% of the credits required for graduation. That can help minimize aggregate spending/borrowing for college, since it becomes easier to find uses for transfer credits and finish in four years or less. But more importantly, choosing a major like that allows your student to add a second major, a minor or two, select a variety of electives, study off-campus.

In short, such majors can be more nimble than their peers in professional and many STEM programs, customizing their education in such a way as to produce a dynamic, distinctive portfolio of skills, knowledge, and experiences.

Schmidt himself is an excellent example of this: as his article demonstrates, he not only possesses all those traditional humanities skills mentioned above, but he is adept at quantitative analysis and data visualization. I don’t know him well enough to know how he cultivated all those skills, but it’s not hard to see how it could happen. Just imagine that your child picks a history major that trains her to frame important questions, conduct research with multiple types of sources, observe change and continuity over time, and then write concisely and effectively about complicated ideas… and meanwhile, also allows her to use some of her remaining 80+ credits to take courses in statistics, programming, graphic design, or journalism.

Schmidt himself is an excellent example of this: as his article demonstrates, he not only possesses all those traditional humanities skills mentioned above, but he is adept at quantitative analysis and data visualization. I don’t know him well enough to know how he cultivated all those skills, but it’s not hard to see how it could happen. Just imagine that your child picks a history major that trains her to frame important questions, conduct research with multiple types of sources, observe change and continuity over time, and then write concisely and effectively about complicated ideas… and meanwhile, also allows her to use some of her remaining 80+ credits to take courses in statistics, programming, graphic design, or journalism.

Say, can I interest you and your child in our department’s new Digital Humanities major? It includes choose-from categories both in the humanities and digital skills…

Before I conclude, let me hasten to add that I don’t think these economic arguments are actually the most important ones to consider. But I’ll turn to the rest of the case for the humanities in my next post…

One thought on “A Counterintuitive Economic Argument for Majoring in the Humanities”

Comments are closed.