Over at Slate writer Ben Schreckinger argues that the seven-day week has outlived its usefulness:

The pattern of living on a seven-day cycle—with one or two of those days set aside for rest—is a relative novelty. Only in the past few centuries, with Western colonization of most of the world, have the majority of human societies adopted it.

The case for the week was never airtight. It’s now weak and getting weaker. Most Westerners no longer observe a weekly Sabbath, and the coordination advantages of keeping everyone on the same uniform schedule have evaporated. So why does this arbitrary time cycle still dictate the rhythm of our lives? Is it time to abolish the week and find a better way to structure time?

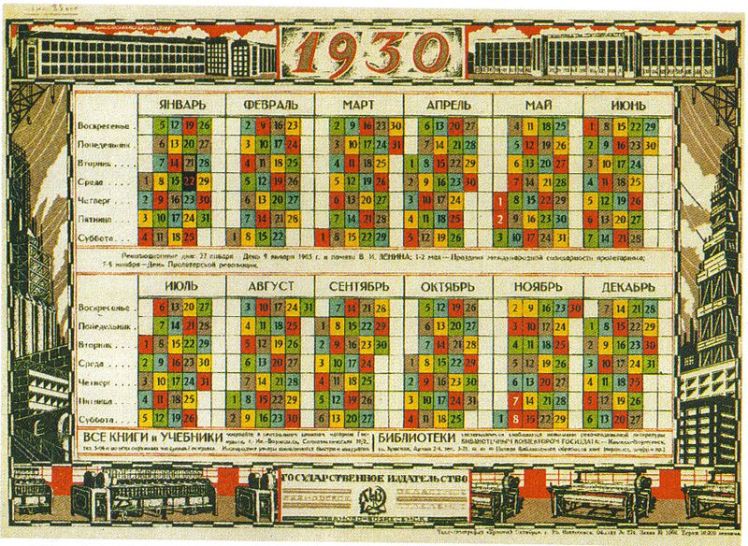

Schreckinger’s case rests on two observations. First, that there’s nothing especially natural about a seven-day week. Unlike the day (light-dark cycle), year (seasonal cycle), and perhaps month (he’s cagier about whether humans have adapted to lunar cycles), the week has no basis in the patterns of nature. Instead, it’s been a useful subdivision of the month based on religious, economic, technological, and cultural factors that vary widely. He rightly points out that human societies have had weeks as short as three (Basque) or five days (Java, the USSR — for a couple years under Stalin) and as long as ten (ancient China, revolutionary France).

So second, our seven-day week derives from ancient Near East religion (Babylonian, then Jewish) with Christianity fixing Sunday as the one day free from work. But Schreckinger observes that “there’s nothing inevitable about the ceaseless repetition of six days of work, one day of rest.” Industrialization eventually led us to the two-day weekend, a convention perhaps fixed by Henry Ford shutting down his factories on Saturday, “in a bid to crystallize an American convention of a two-day weekend full of recreation (that he hoped would involve driving). It worked.”

Schrekinger goes on to observe how the 21st century economy is already enabling workers to divide their time differently. While the mass-production industrial economy of the last century required coordination of workweeks, “The knowledge economy runs differently, and there is no longer such an overwhelming imperative for large numbers of people and goods to come together at the same place at the right times, or for those times to remain uniform across an entire society.” And the workers who take Tuesday off and telecommute on Saturday are the same people opting out of religious observance on Sunday.

(I don’t think he mentions it, but an increasing shift to online education might also disrupt the week as we’ve known it, since there’s no reason that class needs to meet at set times on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, or Tuesday and Thursday, or…)

He doesn’t advocate for a top-down abolition of the seven-day week, but thinks that certain sectors of the economy (Silicon Valley, artists) could lead the way in experimenting: “The year is like a blank slate, and each day a tile that can be arranged into a mosaic — whether in a regular pattern or some other way.”

It’s hard to see this change coming soon, but if it does…

Before Christians bemoan it as the latest evidence of secularization, they should consider two things.

First, that perhaps we played a leading role in making it possible: by individually making decisions about leisure and work time that decentered Sunday as a day set apart from our usual routines. When we decided to stop keeping a day-long sabbath — and when we agreed to a two-day weekend that effectively made Sunday a slightly more sacred version of Saturday, we paved the way for the rethinking of the week itself.

Second, as Western Christians wake up to the fact that they live in post-Christendom societies, they might welcome the advent of a secular week of differing length and composition (or perhaps the disappearance of the week altogether) and yet still keep the seven-day week as Christians — rededicating ourselves to Sunday as the Lord’s Day, a celebration of Resurrection, whether it lines up with a day of work, leisure, or both. (And finding creative ways to keep Sabbath within that seven-day cycle.)

Those of us who follow the liturgical calendar already do this — even as we mark the changing of meteorological, agricultural, commercial, and other seasons, we simultaneously move through Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, and Pentecost. Others among us also subdivide the day according to a pattern that has nothing to do with the industrial or knowledge economy: fixed-hour prayer.

Both practices teach us to live in the world without being fully of it. Of course, learning to straddle and reconcile different sets of weeks wouldn’t be easy (consider how hard it is to keep both secular and religious holidays), but it’s certainly possible. (We’ve long expected our Jewish and Muslim neighbors to figure out how to do it, at least to the extent of having a different day of worship — or set of fixed hours for prayer within the work- or schoolday — than the majority.) And doing so would be another way to remind us that we ought to serve the world rather than rule or be ruled by it.