As historians go, I’m not much of an antiquarian. Since I mostly study the 20th century, I’m little more than a glorified journalist in the eyes of some peers. And I don’t collect first editions or enjoy antiquing. But I’m grateful to my colleague Steve Keillor for passing along excerpts from the 1828 Yale Report. He thought correctly that while I research the history of higher education, I may not have read this antebellum document produced by the faculty of my alma mater.

(Technically, the report was issued by the faculty of Yale College, and I received my degrees from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, which wasn’t founded until 1847 and didn’t award a PhD until the first year of the U.S. Civil War.)

My current research often takes the form of ressourcement, retrieving long-forgotten sources that can illuminate present conditions. In that spirit, the 1828 Yale Report has surprising value as an apology for the liberal arts; it holds up better than might be expected of a document “said to have set back curricular reforms by decades.”

(The Wikipedia editors I’m quoting don’t identify who is “said to have” said this, but it’s a common theme in the history of American education, going back at least as far as Richard Hofstadter and others who viewed the pre-Civil War period as a time of retrenchment and stifling conservatism at many colleges. Revisionists have challenged this characterization, claiming that “traditionalist” antebellum schools like Yale were surprisingly innovative.

Admittedly, even the first part of the report, from which I’m going to draw my material for reflection, praises some elements of 19th century higher education that might not have worn so well, like the notion that colleges should serve in loco parentis, providing a “substitute… for parental superintendence” (p. 6). And the second part insists that classical languages must remain the core of the curriculum, in response to the challenge initiated by Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia, founded in 1819 with a non-classical track available to students. And there’s the “set back… by decades” part, says this modern historian.

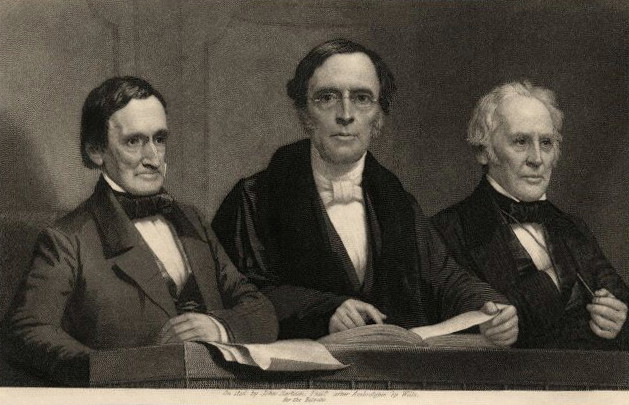

It’s hard, from the perspective of our day, to understand why the authors didn’t think that the principles laid out in Part I would fit a reformed curriculum that allocated more room for modern languages and sciences. Indeed, Part I makes regular allusions to mathematics and sciences, and one of the report’s three authors was chemist Benjamin Silliman, Sr. Another author was the College president, Jeremiah Day, who had originally taught math and natural philosophy. The third, James L. Kingsley, taught Latin and Greek. But I digress…)

Let me quote a few passages from Part I as they illustrate values and principles that still undergird the liberal approach to education: breadth and depth; intellectual rigor; passion and eloquence; and “utility” rightly understood.

Much as my 1st year students would hate to admit it, higher education is designed to be difficult. For example, I’ve come to embrace the fact that many of our students regard our Christianity and Western Culture (CWC) course as “the hardest course” they’ve ever taken. Rather than trying to soften that reputation, I play it up on the first day of class, suggesting that it’s meant to be challenging. Why? Cue our first quotation from the Yale faculty of 1828:

The two great points to be gained in intellectual culture, are the discipline and the furniture of the mind; expanding its powers, and storing it with knowledge. The former of these is, perhaps, the more important of the two. A commanding object, therefore, in a collegiate course, should be, to call into daily and vigorous exercise the faculties of the student. Those branches of study should be prescribed, and those modes of instruction adopted, which are best calculated to teach the art of fixing the attention, directing the train of thought, analyzing a subject proposed for investigation; following, with accurate discrimination, the course of argument; balancing nicely the evidence presented to the judgment; awakening, elevating, and controlling the imagination; arranging, with skill, the treasures which memory gathers; rousing and guiding the powers of genius. All this is not to be effected by a light and hasty course of study; by reading a few books, hearing a few lectures, and spending some months at a literary institution. The habits of thinking are to be formed, by long continued and close application. The mines of science must be penetrated far below the surface, before they will disclose their treasures. If a dexterous performance of the manual operations, in many of the mechanical arts, requires an apprenticeship, with diligent attention for years; much more does the training of the powers of the mind demand vigorous, and steady, and systematic effort. (p. 7)

Now, I have no doubt that students find this task easier and more immediately fulfilling when they are taking classes that most directly interest them. But what of a course, like CWC, that is a required part of the curriculum, taken by nursing, business, science, education, and psychology majors who are not shy in telling me that “history’s not my thing”?

The authors of the 1828 report would offer two responses. First, they hearken back to the fundamental purpose of a liberal education: “to LAY THE FOUNDATION of a SUPERIOR EDUCATION” via “ground work” that “must be broad, and deep, and solid.” The key word here is “broad”; a general curriculum necessarily stretches students past what they might prefer to study in order to develop their whole mind (and heart and soul, I’d add):

In laying the foundation of a thorough education, it is necessary that all the important mental faculties be brought into exercise. It is not sufficient that one or two be cultivated, while others are neglected. A costly edifice ought not to be left to rest upon a single pillar. When certain mental endowments receive a much higher culture than others, there is a distortion in the intellectual character. The mind never attains its full perfection, unless its various powers are so trained as to give them the fair proportions which nature designed…. In the course of instruction in this college, it has been an object to maintain such a proportion between the different branches of literature and science, as to form in the student a proper balance of character. (pp. 7-8)

Second, the authors of the Yale Report suggest that students often sell themselves short:

It is sometimes thought that a student ought not to be urged to the study of that for which he has no taste or capacity. But how is he to know, whether he has a taste or capacity for a science, before he has even entered upon its elementary truths? If he is really destitute of talent sufficient for these common departments of education, he is destined for some narrow sphere of action. But we are well persuaded, that our students are not so deficient in intellectual powers, as they sometimes profess to be; though they are easily made to believe, that they have no capacity for the study of that which they are told is almost wholly useless. (p. 19)

Interestingly, the Yale authors defend the lecture as a crucial answer to such problems. While professing themselves to be “far from believing, that all the purposes of instruction can be best answered by lectures alone,” since that pedagogical approach may enable an overly passive approach to learning, nonetheless the authors find unique benefits to lecturing:

The great advantage of lectures is, that while they call forth the highest efforts of the lecturer, and accelerate his advance to professional eminence; they give that light and spirit to the subject, which awaken the interest and ardor of the student. They may place before him the principles of science, in the attractive dress of living eloquence. (p. 10)

This is highly unfashionable but often true. One of the key moments of my professional development was realizing that, important as it is for me to draw on other techniques, at a certain point I need to accept that I’m most gifted as a lecturer and that those gifts play an important role in student learning. Because when lectures given with forethought, passion, and eloquence share “that light and spirit… which awaken the interest and ardor of the student,” they are tapping into something that the great philosopher of education Parker Palmer once observed:

Students will often say that their favorite teachers are ones who are enthusiastic about their subjects even if they are not masters of teaching technique. More is happening here than the simple contagion of enthusiasm. Such teachers overcome the students’ fear of meeting this stranger, this subject, by revealing the friendship that binds subject and teacher. Students are affirmed by the fact that this teacher wants them to know and be known by this valued friend in the context of a well-established love. (To Know As We Are Known, pp. 103-104)

And if students remain untouched by the passion of professors and the rigors of coursework, the Yale authors argue that it probably isn’t their fault: “Parents are little aware to what embarrassments and injury they are subjecting their sons [no daughters at Yale College for another 141 years], by urging them forward to a situation for which they are not properly qualified” (p. 26). Parents who “seem frequently more solicitous for the name of an education, than the substance” also help convince their chidren “that the study of any thing for which they have not an instinctive relish, or which requires vigorous and continued effort, or which is not immediately connected with their intended professional pursuits, is of no practical utility. They of course remain ignorant of that which they think not worth the learning” (pp. 26-27).

And what of the assumption that liberal arts are “almost wholly useless,” that non-professional studies are “of no practical utility”? In light of the rampant attempts in our own age to devalue liberal arts, it’s worth quoting this part of the 1828 Report at some considerable length:

Why, it may be asked, should a student waste his time upon studies which have no immediate connection with his future profession? Will chemistry enable him to plead at the bar, or conic sections qualify him for preaching, or astronomy aid him in the practice of physic? Why should not his attention be confined to the subject which is to occupy the labors of his life? In answer to this, it may be observed, that there is no science which does not contribute its aid to professional skill. “Every thing throws light upon every thing.” The great object of a collegiate education, preparatory to the study of a profession, is to give that expansion and balance of the mental powers, those liberal and comprehensive views, and those fine proportions of character, which are not to be found in him whose ideas are always confined to one particular channel. When a man has entered upon the practice of his profession, the energies of his mind must be given, principally, to its appropriate duties. But if his thoughts never range on other subjects, if he never looks abroad on the ample domains of literature and science, there will be a narrowness in his habits of thinking, a peculiarity of character, which will be sure to mark him as a man of limited views and attainments. Should he be distinguished in his profession, his ignorance on other subjects, and the defects of his education, will be the more exposed to public observation. On the other hand, he who is not only eminent in professional life, but has also a mind richly stored with general knowledge, has an elevation and dignity of character, which gives him a commanding influence in society, and a widely extended sphere of usefulness. His situation enables him to diffuse the light of science among all classes of the community. Is a man to have no other object, than to obtain a living by professional pursuits? Has he not duties to perform to his family, to his fellow citizens, to his country; duties which require various and extensive intellectual furniture? (pp. 14-15)

Pointedly excluding “Professional studies” from their curriculum, the authors instead stress that their

…object is not to finish [the student’s] education; but to lay the foundation, and to advance as far in rearing the superstructure, as the short period of his residence here will admit. If he acquires here a thorough knowledge of the principles of science, he may then, in a great measure, educate himself. He has, at least, been taught how to learn…. Our object is not to teach that which is peculiar to any one of the professions; but to lay the foundation which is common to them all. (p. 14)