Belatedly (and too quickly), let me wrap up this series on European museums and their role in presenting the history of the First World War. (Read the first post here.) In previous posts, I’ve employed Jay Winter’s phrase “cathedrals of the modern world” as an especially lofty vision of what museums could or should be. Today we’ll touch on two Continental museums, one of which aspires to Winter’s ideal and one of which couldn’t be further from a cathedral, of any sort. Which is part of its charm. But first…

Les Invalides

The Invalides complex in Paris (get out at the Invalides or École Militaire Métro stops) is easy to mistake for a cathedral: its grand golden dome (seen above from our lovely hotel room down the street — if you’re looking to indulge yourself a bit without breaking your budget, you could do worse than the Hôtel de France Invalides!) covers what used to be the chapel of a military hospital. For most tourists, the visit could start and stop beneath that dome, since it provides eternal, opulent rest to Napoleon and other military heroes from throughout French history. WWI fans will want to see the tomb of Ferdinand Foch (right), the French general who became the first Allied commander late in the war and oversaw the triumph over the Germans on the Western Front.

The Invalides complex in Paris (get out at the Invalides or École Militaire Métro stops) is easy to mistake for a cathedral: its grand golden dome (seen above from our lovely hotel room down the street — if you’re looking to indulge yourself a bit without breaking your budget, you could do worse than the Hôtel de France Invalides!) covers what used to be the chapel of a military hospital. For most tourists, the visit could start and stop beneath that dome, since it provides eternal, opulent rest to Napoleon and other military heroes from throughout French history. WWI fans will want to see the tomb of Ferdinand Foch (right), the French general who became the first Allied commander late in the war and oversaw the triumph over the Germans on the Western Front.

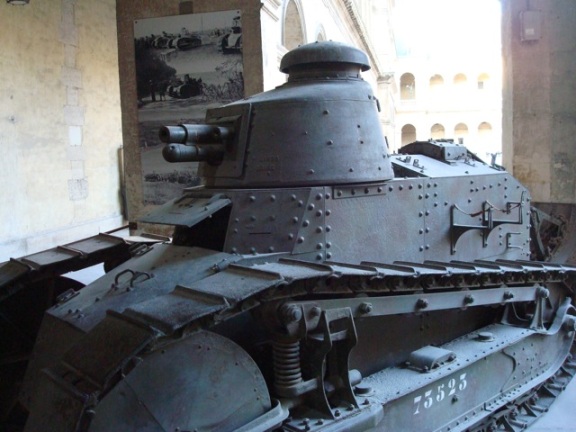

Then they’ll want to go inside, head upstairs, and visit the modern military history museum and its well-designed, extensive WWI and WWII exhibits. Much of it echoes the themes and style of the Imperial War Museum: an abundance of artifacts (note to English-speaking visitors: while there are English descriptions at various key points in each room, many items themselves have only French labels; it might be worth the euros to pick up an audio guide). My wife especially appreciated the clever use of film projectors and space, plus the interactive maps early in the WWI exhibit demonstrating the advances back and forth along the Western Front.

But after having seen the IWM, it takes a lot to stand out. And so the French museum comes off as more than competent, but less than memorable. From the WWI section, I was most struck by the explicit reference to the “genocide” inflicted on the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. (See my earlier post on the ongoing debate in France over a law criminalizing genocide denial or minimalization.) As far as I can remember, the IWM included no such language in its section on the War in the Middle East… (Please correct me if I’m wrong about this.)

But, in all honesty, I was most interested to see how the Invalides presented World War II, a war remembered with understandable ambivalence by most French citizens. For the most part, the curators did a splendid job of presenting a truly international story of the conflict, while reserving special attention for the phenomena of resistance and collaboration in occupied France (the former, not surprisingly, receiving rather more of the spotlight). But they couldn’t entirely escape the French nationalist obsession with La Gloire. In the section explaining what historian-resister Marc Bloch called the “strange defeat” of May-June 1940, when the French military crumbled beneath the onslaught of the German Blitzkrieg, the description stressed that the French did inflict tens of thousands of casualties on the Wehrmacht. Which is true: except that the table of casualties right next to this explanation makes clear that French losses were two to three times as high.

In the end, I actually found a much smaller, more old-fashioned museum much more memorable…

Sanctuary Wood Museum

In a forest outside the Belgian city of Ieper (Ypres), near the strategic point known as Hill 62, stands a curious museum with a fascinating history. During the many battles around this salient on the Western Front, civilians were evacuated. They returned in 1919 to an uncertain future. One of the returnees was a farmer who reclaimed his land and began to plow his fields, but decided to preserve a section of the British trenches as the soldiers had left them. (pictured above)

Most unpreserved trenches from WWI look like these near the South African memorial at Delville Wood, part of the Somme battlefields in northern France. While the slats of wood the British used to reinforce the holes they dug have, of course, rotted away and been replaced, the trenches at Sanctuary Wood are otherwise much as they would have been back in 1914-1918 — right down to the muddy clay so famously associated with this portion of the Western Front. The museum — wisely — suggests bringing boots, especially if you want to go through the four-foot high tunnel uncovered by British engineers in the 1980s.

While the slats of wood the British used to reinforce the holes they dug have, of course, rotted away and been replaced, the trenches at Sanctuary Wood are otherwise much as they would have been back in 1914-1918 — right down to the muddy clay so famously associated with this portion of the Western Front. The museum — wisely — suggests bringing boots, especially if you want to go through the four-foot high tunnel uncovered by British engineers in the 1980s.

Of course, to really get a sense of what it would have been like during the war, you have to imagine away all the trees that eventually regrew. At the Sanctuary Wood trenches, one original tree still stands (left): reduced to a bullet- and shrapnel-riddled stump and adorned with the poppy flowers and wooden crosses that are ubiquitous around “Flanders Fields.”

Of course, to really get a sense of what it would have been like during the war, you have to imagine away all the trees that eventually regrew. At the Sanctuary Wood trenches, one original tree still stands (left): reduced to a bullet- and shrapnel-riddled stump and adorned with the poppy flowers and wooden crosses that are ubiquitous around “Flanders Fields.”

Eventually, the farmhouse near these preserved trenches itself became a small, private museum — and nothing about it would evoke the grandeur of Winter’s “cathedrals of the modern world.” But that’s its charm. Practically every square inch is covered with objects or images, some of it approaching what might be called WWI kitsch, but there are no multimedia presentations or computer animation. (Though one of the best exhibits does feature another kind of technology that was once cutting-edge: early 20th century photo viewers showing three-dimensional scenes of the war.) If you’re more social than me, you can order a wheat beer at the bar and chat up the owner and his regulars for their stories, but don’t expect to find audio, visual, or textual descriptions in the museum itself. At times, it feels less like artifacts have been preserved and presented with any attempt at making meaning of a world-changing event than that you’re peeking in on the life’s work of a souvenir collector (or pack rat).

At the same time, the sense that this was the home of someone deeply affected by the war endures. And so the museum also feels like an amplified version of another phenomenon Winter describes in his great cultural history of WWI remembrance. While much attention on the commemoration of the First World War (my own included) focuses on memorials sponsored by governments and museums influenced by scholarship, Winter reminds us that “Commemoration also [and earliest] happened on a much more intimate level, through the preservation in households of possessions, photographs, personal signatures of the dead.” (Sites of memory, sites of mourning, p. 51)

At the same time, the sense that this was the home of someone deeply affected by the war endures. And so the museum also feels like an amplified version of another phenomenon Winter describes in his great cultural history of WWI remembrance. While much attention on the commemoration of the First World War (my own included) focuses on memorials sponsored by governments and museums influenced by scholarship, Winter reminds us that “Commemoration also [and earliest] happened on a much more intimate level, through the preservation in households of possessions, photographs, personal signatures of the dead.” (Sites of memory, sites of mourning, p. 51)

It’s well that museums are increasingly professional, and that their staff are conscious about the challenges of serving at the intersection of public memory and academic inquiry. But as the last of the war’s veterans die away and the commemoration of the war loses its original connection with the mourning of families like those who submitted epitaphs for British graves, it’s strangely refreshing to enter the musty air of the Sanctuary Wood Museum. If not cathedral-like, it is nonetheless a place where, in Winter’s words, “sacred issues are expressed and where people come to reflect on them.”